Design Build vs. Design Bid Build

Written by

Published on

April 3, 2022

Table of contents

Whereas for decades public and private projects were entirely built using one project delivery method—design bid build—project owners today can choose from a wide range of options to get the most value out of the project process.

As newer project delivery methods grow in popularity, they will continue to present new opportunities, and new challenges, for successful utility coordination. When setting their utility strategy, project owners, general contractors, engineers, estimators, designers, and service providers will want to make sure they’re maximizing the potential benefits of each project delivery method. In this post, we’ll take a deep dive into the two most common project delivery methods— Design Bid Build (DBB) and Design Build— and look at their relationship with utilities and utility strategy.

In this post, we’ll cover the following points:

- What is a project delivery method? What are the different phases of a delivery method?

- What exactly are Design Bid Build and Design Build? What are the key differences?

- What are the key takeaways for utility stakeholders when using Design-Bid-Build and Design-Build?

- What can utility mapping contribute to both Design Bid Build and Design Build contracts?

What is a project delivery method?

According to the Design-Build Institute of America, a Project Delivery method is “a comprehensive process including planning, design and construction required to execute and complete…a project.” In short, a project delivery method is the process from start to finish of a project. It includes the initial conception and planning, the procurement process, design, and construction until completion.

While in the past nearly all projects in the public and private sector were all Design-Bid-Build, in recent decades more and more public and private sector project owners are adopting and integrating other project delivery methods. In this article, we’ll discuss two—Design Bid Build and Design Build—but there are other methods (like GCAR and PPP) that are also increasingly common.

What are the different project phases?

Delivery methods are broken into a few distinct project phases. The way that these phases are organized and overlap—and the different stakeholders involved in each phase—is the key difference between different types of project delivery methods. The different structures of a delivery method can have big implications for subsurface utility strategy.

In any project, there are at least the conceptual, pre-design, procurement, design, and construction phases.

The Conceptual Phase:

The conceptual phase involves taking a project need and advancing it to a general scope of work in support of a request for funding authorization. The major tasks are determining the project’s alignment/footprint, identifying stakeholders, and financial analysis to calculate either the benefit-cost ratio (public) or the return on investment and payback period (private). The conceptual phase ends with authorization of funding to advance the project’s design. The design will be roughly 5% to 10% complete. In this phase, the project owner and estimators need to understand subsurface and environmental conditions, and to begin factoring in potential utility conflicts into the project schedule.

The Pre-Design Phase (up to 30% completion):

The pre-design phase involves preliminary engineering and design necessary to refine the project’s scope of work to a point where environmental permit applications can be submitted, real estate/rights of way acquisition can commence, top-down cost estimates can be completed to validate the project’s viability, and public outreach can commence. The design will be roughly 25% to 30% complete. In the pre-design phase, project owners, estimators, and potentially design builders already need to have a good understanding of subsurface utility conditions so that they can begin utility coordination and get a good understanding of potential costs.

The Procurement Phase:

The procurement phase involves advertising, accepting/evaluating bids, tender offers, or proposals depending on project delivery method, and awarding the final construction contract. During the procurement phase, understanding the utility landscape is crucial, as it influences the complexity, price, risk, and contingency of the bids.

The Design Phase:

The design phase includes completing engineering and design necessary to the point where procurement of the construction contractor can commence, and so that bottom-up cost estimates can be completed. The design will be 100% complete. In the design phase, designers and design builders need quality utility data to make sure that the design matches conditions in the field—and to avoid potential delays and costly redesigns.

The Construction Phase:

The construction phase involves building, inspecting, commissioning, and accepting the project. At the conclusion of the construction phase, engineers need to submit updated utility data that may have changed during the project.

How do Design Bid Build and Design Build work? What’s the difference between them?

The two most common types of delivery methods are Design-Bid Build (DBB), and Design Build (DB).

Design Bid Build (DBB):

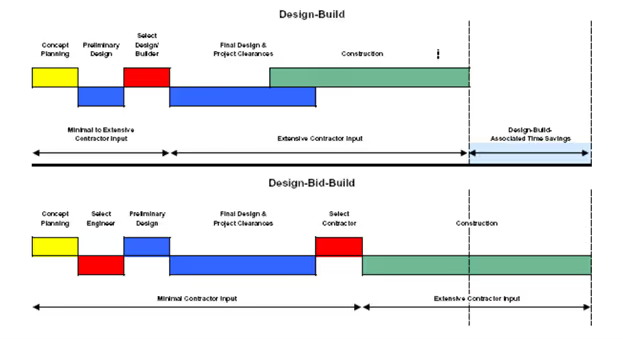

In Design Bid Build (DBB) the conceptual, pre-design, and design phases are all completed before the procurement phase is started. In the procurement phase, contractors can bid on the project, and construction follows procurement. The construction contractor is not involved in the design process.

Sometimes, but not always, projects that are simpler, more predictable, and smaller scale will take place under Design-Bid-Build methods. The majority of public sector projects are still built using Design-Bid Build methods, as are many private sector projects.

Design Build (DB):

In Design Build (DB), the conceptual and pre-design phases are completed before the procurement phase is started. Then a request for qualifications (RFQ) is issued and the best qualified bidders are short-listed. The short-listed bidders are issued a request for proposals (RFP) which requires them to submit a technical design proposal and a corresponding price proposal. The DB contract is awarded and the design phase commences. When elements of the design reach a point where they are complete, the owner has the option to commence the construction phase before completing the final design.

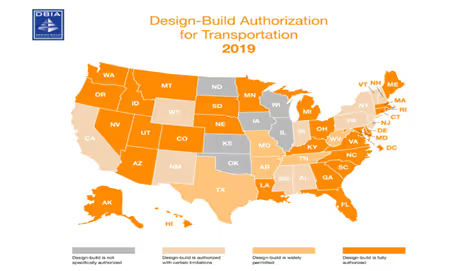

Design Build contracts are a growing segment of the market—according to one study, DB contracts represent 43% of all construction between 2018-2021. These projects are most often used in large “mega” projects, and nearly all states in the United States allow Design Build contracts. However, some states still have legal limitations on the number and scale of DB contracts that can be awarded at any given time. In Texas for example, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) can only use design-build contracts for highway projects with a construction cost of $150 million or more and limits the number of Design-Build contracts to no more than 6 every two years.

The figure below shows the legal status of Design Build contracts by state as of 2019.

Even with these limitations, the popularity of Design Build projects will likely continue to grow across the country, since they offer some significant benefits for project owners and design builders.

What is so different between Design Bid Build and Design Build?

Design Bid Build contracts were long the industry standard and remain the most common project delivery method in the public sector. In a Design Bid Build contract, the process is linear and discrete—when one phase ends, the next begins. This creates an organized and logical workflow, creates a clear and competitive bidding process, and can put more control in the hands of project owners. On the other hand, this process can be slower, and it doesn’t integrate contractors until relatively late in the process. That can lead to well-known problems: disputes over utility relocation, environmental permitting, design disagreements and costly redesigns—and can leave the project owner holding much of the risk.

In a typical Design Build contract, a design builder is involved in the process from a much earlier stage. While the conceptual and pre-design stage may still take place without much contractor input, the design builder is already heavily involved from the beginning of the design stage. This can create, in theory, a more efficient process, with contractors offering input earlier in the process and minimizing costly redesigns. Crucially, construction work can begin while the final design is still being completed, which can significantly shorten project duration.

According to the Texas Department of Transportation , the design build process offers other possible benefits:

- A selection process that considers price and other factors to find the best value bidder.

- A single point of responsibility for design and construction—which bolsters collaboration between all parties.

- Fixed price contracting and cost certainty.

- A speedier overall process by allowing design, construction, and utility relocation to overlap.

- Transferring many of the risks from design errors and schedule delays to a private sector party.

A 2006 study by the US Federal Highway Administration found that, in some cases, design build contracts can generate significant cost (an average of 3%) and time (an average 14% shorter duration) savings. These types of projects can yield major time savings by allowing the project managers to start building even while the final details of the design are being finished.

What are the key takeaways for utility stakeholders in using Design-Bid-Build (DBB) and Design Build (DB)?

Both Design-Bid-Build and Design-Build projects offer opportunities for utility coordination from the outset–reducing the risk of project delays and costly utility strikes. But there are a few key differences between the two methods.

In Design-Bid-Build projects, getting a clear understanding of utility risk as early in the project as possible —and well before procurement—is crucial. The Colorado STA suggests that project owners identify and mitigate utilities risk, environmental clearances, Right of Way (ROW) clearances, and relevant third parties (railroads, public utility commissions) before the procurement stage. Since the project owner chooses the designer and the construction contractor separately, much of the ultimate responsibility (and risk) for utility strategy can fall back to them.

To minimize this risk as much as possible, project owners can make use of utility mapping in the conception and pre-design phases.

In design build projects, much of the risk is passed on from the project owner to the design-builder. In these types of projects, careful coordination between the project owner and the design-builder is key to keeping down risk pricing. The Colorado STA recommend that even in design-build projects, project owners should conduct their own utility investigations. Further, stakeholders should make sure agreements with private utilities are already set before procurement—as design builders have a tough time pricing these risks beforehand. Some of the design and construction risk for public utilities can be passed on to the design builder—so long as it is clearly spelled out in the contract terms.

“DB provides the opportunity to share the risk between the owner and the contractor in a manner that better manages the overall risk, but care must be exercised to properly allocate the risk and to minimize it through advanced coordinated and design development.”

Design builders and their teams need to be careful that the time pressure of Design-Build doesn’t lead them to skip over setting a coherent utility strategy. If anything, having a clear plan for addressing utilities conflicts from the very first phases of a Design-build project is especially important.

As early as possible, project owners and contractors need to acquire as much accurate utility mapping information as they can to inform early conceptual and design decisions. Since construction might already be underway even as the later elements of the design are still being completed, design-builders risk needing to redesign on the fly if as-built conditions aren’t as expected.

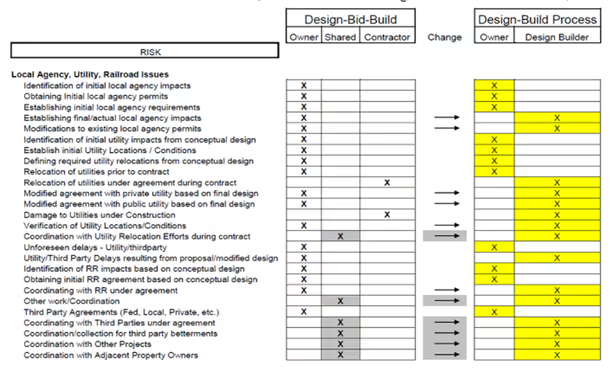

In general— it’s also crucial in a design-build project to make sure that all aspects and attributions of utility risk are clearly defined in the contract terms between the project owner and the design builder. The following table from the Alaska, and Washington State DOTs show how risk allocation can drastically differ depending on the contract type.

These tables demonstrate how, in design bid build project, the project owner can be ultimately responsible for most of the utility management. For a project owner, it’s crucial to begin addressing these issues already from the beginning of the conceptual and pre-design stages.

With design build, the design builder can be taking on a much larger or even the entire share of the risk of utility relocation, utility strikes, and delays. They also can be responsible for managing much more of the utility coordination than under a design bid build contract—including both with private utilities, third parties, and other projects in adjacent areas. This only raises the importance for design builders of tackling utility challenges from the outset.

By setting a utility strategy from the outset of any project, getting a clear, in-depth look at the subsurface utility conditions in the conceptual and pre-design phases, and putting in the time early to address utility coordination, all stakeholders can minimize risk and make the most of both project delivery methods.

What can utility mapping contribute to both Design Bid Build and Design Build contracts?

In both Design Bid Build and Design Build projects, project owners, general contractors, designers, engineers, and service providers can get a lot of value by using utility mapping as part of their utility strategy.

In design bid build projects, project owners that use utility mapping to get a clear and comprehensive look at subsurface utility conditions in the conceptual and pre-design phases can better price overall risk, reduce contingency, and create a better bidding process. Designers and engineers with quality utility information in front of them prior to bidding can anticipate and avoid utility conflicts and costly future re-designs—reducing the risk for delays and unpleasant surprises once a constructer is chosen and begins work. And contractors bidding on designs can be more confident that the subsurface utility conditions in the design match the reality they’ll find when they begin work.

Subsurface utility mapping is just as if not more important in design build projects. Design builders that understand subsurface conditions can make more competitive bids, streamline the design process, and prevent utility conflicts from causing unnecessary delays.

With a clear image of subsurface conditions in hand from the outset, design builders can also better allocate utility risk and responsibility in the initial contract. Utility mapping can also reduce some of the the added time pressure of large design build projects, by giving design builders more confidence in their ongoing designs as they begin construction.

By integrating subsurface utility mapping into the project delivery process, all stakeholders can set themselves up for a successful project.

Recent blog posts

Our Newsletter

Join 7k infrastructure professionals

Get monthly insights on ways to build smarter, faster and safer with Utility AI.